Could the Evolutionary Theory of the Development of Humankind Include the Ability to Make Art?

The supernatural is phenomena or entities that are not subject to the laws of nature. It is derived from Medieval Latin supernaturalis, from Latin super- (in a higher place, beyond, or outside of) + natura (nature)[ane] Though the corollary term "nature", has had multiple meanings since the ancient globe, the term "supernatural" emerged in the medieval menstruum[two] and did not exist in the ancient globe.[3]

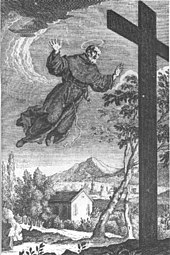

The supernatural is featured in folklore and religious contexts,[4] but can also feature every bit an caption in more secular contexts, equally in the cases of superstitions or conventionalities in the paranormal.[5] The term is attributed to non-concrete entities, such as angels, demons, gods, and spirits. It also includes claimed abilities embodied in or provided by such beings, including magic, telekinesis, levitation, precognition, and extrasensory perception.

The philosophy of naturalism contends that nothing exists beyond the natural world, and as such approaches supernatural claims with skepticism.[6]

Etymology and history of the concept [edit]

Occurring as both an adjective and a noun, descendants of the modern English chemical compound supernatural enter the language from two sources: via Middle French (supernaturel) and directly from the Middle French'southward term's antecedent, mail service-Classical Latin (supernaturalis). Post-classical Latin supernaturalis showtime occurs in the 6th century, equanimous of the Latin prefix super- and nātūrālis (see nature). The earliest known appearance of the word in the English occurs in a Middle English translation of Catherine of Siena'south Dialogue (orcherd of Syon, around 1425; Þei haue non þanne þe supernaturel lyȝt ne þe liȝt of kunnynge, bycause þei vndirstoden it not).[vii]

The semantic value of the term has shifted over the history of its use. Originally the term referred exclusively to Christian understandings of the globe. For instance, as an adjective, the term tin can mean "belonging to a realm or system that transcends nature, as that of divine, magical, or ghostly beings; attributed to or thought to reveal some force across scientific understanding or the laws of nature; occult, paranormal" or "more than what is natural or ordinary; unnaturally or extraordinarily great; aberrant, boggling". Obsolete uses include "of, relating to, or dealing with metaphysics". As a noun, the term can mean "a supernatural being", with a especially potent history of employment in relation to entities from the mythologies of the ethnic peoples of the Americas.[vii]

History of the concept [edit]

The ancient globe had no word that resembled "supernatural".[3] Dialogues from Neoplatonic philosophy in the tertiary century AD contributed the evolution of the concept the supernatural via Christian theology in later centuries.[viii] The term nature had existed since antiquity with Latin authors like Augustine using the word and its cognates at to the lowest degree 600 times in City of God. In the medieval period, "nature" had ten different meanings and "natural" had eleven different meanings.[2] Peter Lombard, a medieval scholastic in the 12th century, asked about causes that are across nature, in that how there could exist causes that were God's alone. He used the term praeter naturam in his writings.[ii] In the scholastic period, Thomas Aquinas classified miracles into three categories: "above nature", "beyond nature", and "against nature". In doing and so, he sharpened the distinction between nature and miracles more than than the early on Church building Fathers had washed.[two] Equally a effect, he had created a dichotomy of sorts of the natural and supernatural.[8] Though the phrase "supra naturam" was used since the 4th century AD, information technology was in the 1200s that Thomas Aquinas used the term "supernaturalis" and despite this, the term had to wait until the end of the medieval period before it became more popularly used.[ii] The discussions on "nature" from the scholastic period were various and unsettled with some postulating that even miracles are natural and that natural magic was a natural part of the world.[ii]

Epistemology and metaphysics [edit]

The metaphysical considerations of the beingness of the supernatural can be difficult to approach as an exercise in philosophy or theology because any dependencies on its antonym, the natural, will ultimately have to exist inverted or rejected. Ane complicating gene is that there is disagreement about the definition of "natural" and the limits of naturalism. Concepts in the supernatural domain are closely related to concepts in religious spirituality and occultism or spiritualism.

For sometimes we utilize the word nature for that Author of nature whom the schoolmen, harshly enough, call natura naturans, every bit when it is said that nature hath fabricated man partly corporeal and partly immaterial. Sometimes we mean past the nature of a thing the essence, or that which the schoolmen scruple non to call the quiddity of a thing, namely, the aspect or attributes on whose score information technology is what information technology is, whether the thing be corporeal or not, every bit when we attempt to ascertain the nature of an angle, or of a triangle, or of a fluid body, as such. Sometimes we have nature for an internal principle of motility, as when we say that a stone allow fall in the air is by nature carried towards the centre of the globe, and, on the contrary, that fire or flame does naturally move upwards toward firmament. Sometimes we understand past nature the established form of things, equally when we say that nature makes the nighttime succeed the day, nature hath made respiration necessary to the life of men. Sometimes nosotros take nature for an aggregate of powers belonging to a body, especially a living one, as when physicians say that nature is strong or weak or spent, or that in such or such diseases nature left to herself will exercise the cure. Sometimes we accept nature for the universe, or system of the corporeal works of God, every bit when it is said of a phoenix, or a chimera, that there is no such thing in nature, i.eastward. in the world. And sometimes too, and that most ordinarily, we would limited past nature a semi-deity or other strange kind of being, such as this discourse examines the notion of.

And likewise these more absolute acceptions, if I may then telephone call them, of the word nature, information technology has divers others (more than relative), as nature is wont to be set or in opposition or contradistinction to other things, equally when nosotros say of a stone when it falls downwards that it does information technology past a natural movement, just that if information technology exist thrown upward its motility that style is tearing. And so chemists distinguish vitriol into natural and fictitious, or made by art, i.e. by the intervention of human ability or skill; and then it is said that water, kept suspended in a sucking pump, is not in its natural identify, as that is which is stagnant in the well. We say besides that wicked men are still in the state of nature, simply the regenerate in a state of grace; that cures wrought past medicines are natural operations; but the miraculous ones wrought past Christ and his apostles were supernatural.[9]

—Robert Boyle, A Free Enquiry into the Vulgarly Received Notion of Nature

Nomological possibility is possibility under the bodily laws of nature. Well-nigh philosophers since David Hume take held that the laws of nature are metaphysically contingent—that at that place could take been different natural laws than the ones that actually obtain. If and then, and then it would not be logically or metaphysically impossible, for case, for yous to travel to Alpha Centauri in ane day; information technology would just have to exist the instance that you could travel faster than the speed of light. But of course at that place is an important sense in which this is non nomologically possible; given that the laws of nature are what they are. In the philosophy of natural scientific discipline, impossibility assertions come to be widely accepted as overwhelmingly probable rather than considered proved to the indicate of being unchallengeable. The ground for this strong acceptance is a combination of extensive evidence of something not occurring, combined with an underlying scientific theory, very successful in making predictions, whose assumptions lead logically to the conclusion that something is impossible. While an impossibility exclamation in natural science can never be absolutely proved, it could be refuted past the ascertainment of a single counterexample. Such a counterexample would require that the assumptions underlying the theory that implied the impossibility be re-examined. Some philosophers, such equally Sydney Shoemaker, have argued that the laws of nature are in fact necessary, not contingent; if so, and so nomological possibility is equivalent to metaphysical possibility.[10] [11] [12]

The term supernatural is often used interchangeably with paranormal or preternatural—the latter typically express to an adjective for describing abilities which appear to exceed what is possible within the boundaries of the laws of physics.[13] Epistemologically, the relationship between the supernatural and the natural is indistinct in terms of natural phenomena that, ex hypothesi, violate the laws of nature, in so far as such laws are realistically accountable.

Parapsychologists use the term psi to refer to an assumed unitary force underlying the phenomena they study. Psi is defined in the Periodical of Parapsychology as "personal factors or processes in nature which transcend accustomed laws" (1948: 311) and "which are not-physical in nature" (1962:310), and it is used to cover both extrasensory perception (ESP), an "sensation of or response to an external issue or influence not apprehended by sensory means" (1962:309) or inferred from sensory cognition, and psychokinesis (PK), "the straight influence exerted on a physical organization by a field of study without any known intermediate energy or instrumentation" (1945:305).[14]

—Michael Winkelman, Current Anthropology

Views on the "supernatural" vary, for example it may be seen as:

- indistinct from nature. From this perspective, some events occur according to the laws of nature, and others occur according to a divide set of principles external to known nature. For example, in Scholasticism, it was believed that God was capable of performing any phenomenon then long as information technology didn't lead to a logical contradiction. Some religions posit immanent deities, notwithstanding, and do not have a tradition analogous to the supernatural; some believe that everything anyone experiences occurs by the volition (occasionalism), in the mind (neoplatonism), or as a part (nondualism) of a more fundamental divine reality (platonism).

- wrong human attribution. In this view all events take natural and merely natural causes. They believe that human beings accredit supernatural attributes to purely natural events, such as lightning, rainbows, floods, and the origin of life.[15] [16]

Anthropological studies [edit]

Anthropological studies across cultures indicate that people do non concord or use natural and supernatural explanations in a mutually exclusive or dichotomous fashion. Instead, the reconciliation of natural and supernatural explanations is normal and pervasive across cultures.[17] Cross cultural studies indicate that there is coexistence of natural and supernatural explanations in both adults and children for explaining numerous things well-nigh the globe such as illness, death, and origins.[xviii] [19] Context and cultural input play a big role in determining when and how individuals incorporate natural and supernatural explanations.[xx] The coexistence of natural and supernatural explanations in individuals may be the outcomes two distinct cognitive domains: one concerned with the physical-mechanical relations and another with social relations.[21] Studies on ethnic groups have allowed for insights on how such coexistence of explanations may part.[22]

Supernatural concepts [edit]

Deity [edit]

A deity ( or )[23] is a supernatural being considered divine or sacred.[24] The Oxford Dictionary of English defines deity equally "a god or goddess (in a polytheistic religion)", or annihilation revered as divine.[25] C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greater than those of ordinary humans, merely who interacts with humans, positively or negatively, in ways that carry humans to new levels of consciousness, across the grounded preoccupations of ordinary life."[26] A male person deity is a god, while a female person deity is a goddess.

Religions can be categorized by how many deities they worship. Monotheistic religions accept just one deity (predominantly referred to as God),[27] [28] polytheistic religions take multiple deities.[29] Henotheistic religions take one supreme deity without denying other deities, considering them as equivalent aspects of the same divine principle;[thirty] [31] and nontheistic religions deny any supreme eternal creator deity just accept a pantheon of deities which alive, die, and are reborn just like any other being.[32] : 35–37 [33] : 357–358

Various cultures have conceptualized a deity differently than a monotheistic God.[34] [35] A deity demand not be omnipotent, omnipresent, omniscient, omnibenevolent or eternal,[34] [35] [36] The monotheistic God, however, does have these attributes.[37] [38] [39] Monotheistic religions typically refer to God in masculine terms,[40] [41] : 96 while other religions refer to their deities in a variety of ways – masculine, feminine, androgynous and gender neutral.[42] [43] [44]

Historically, many aboriginal cultures – such every bit Ancient India Aboriginal Egyptian, Ancient Greek, Aboriginal Roman, Nordic and Asian civilization – personified natural phenomena, variously as either their witting causes or only their effects, respectively.[45] [46] [47] Some Avestan and Vedic deities were viewed as ethical concepts.[45] [46] In Indian religions, deities have been envisioned equally manifesting inside the temple of every living being's torso, as sensory organs and mind.[48] [49] [fifty] Deities take also been envisioned equally a form of existence (Saṃsāra) subsequently rebirth, for human beings who gain merit through an ethical life, where they become guardian deities and live blissfully in heaven, but are as well subject to death when their merit runs out.[32] : 35–38 [33] : 356–359

Angel [edit]

An angel is generally a supernatural existence found in various religions and mythologies. In Abrahamic religions and Zoroastrianism, angels are often depicted every bit benevolent celestial beings who human activity as intermediaries between God or Heaven and Earth.[51] [52] Other roles of angels include protecting and guiding man beings, and carrying out God's tasks.[53] Within Abrahamic religions, angels are often organized into hierarchies, although such rankings may vary between sects in each religion, and are given specific names or titles, such as Gabriel or "Destroying angel". The term "affections" has as well been expanded to various notions of spirits or figures found in other religious traditions. The theological study of angels is known every bit "angelology".

In fine art, angels are usually depicted as having the shape of human beings of boggling beauty;[54] [55] they are often identified using the symbols of bird wings,[56] halos,[57] and light.

Prophecy [edit]

Prophecy involves a process in which messages are communicated by a god to a prophet. Such messages typically involve inspiration, interpretation, or revelation of divine will concerning the prophet'due south social earth and events to come (compare divine knowledge). Prophecy is not limited to any one civilisation. It is a common property to all known aboriginal societies around the globe, some more than others. Many systems and rules almost prophecy take been proposed over several millennia.

Revelation [edit]

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some grade of truth or knowledge through advice with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Some religions have religious texts which they view as divinely or supernaturally revealed or inspired. For example, Orthodox Jews, Christians and Muslims believe that the Torah was received from Yahweh on biblical Mountain Sinai.[58] [59] Most Christians believe that both the Old Attestation and the New Attestation were inspired by God. Muslims believe the Quran was revealed past God to Muhammad word by word through the angel Gabriel (Jibril).[60] [61] In Hinduism, some Vedas are considered apauruṣeya , "not human being compositions", and are supposed to have been straight revealed, and thus are called śruti, "what is heard". The fifteen,000 handwritten pages produced by the mystic Maria Valtorta were represented every bit straight dictations from Jesus, while she attributed The Book of Azariah to her guardian affections.[62] Aleister Crowley stated that The Book of the Police force had been revealed to him through a higher being that called itself Aiwass.

A revelation communicated by a supernatural entity reported as beingness present during the upshot is called a vision. Direct conversations between the recipient and the supernatural entity,[63] or physical marks such equally stigmata, have been reported. In rare cases, such as that of Saint Juan Diego, physical artifacts accompany the revelation.[64] The Roman Cosmic concept of interior locution includes merely an inner phonation heard by the recipient.

In the Abrahamic religions, the term is used to refer to the process past which God reveals knowledge of himself, his will, and his divine providence to the world of human beings.[65] In secondary usage, revelation refers to the resulting homo knowledge about God, prophecy, and other divine things. Revelation from a supernatural source plays a less important role in some other religious traditions such as Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism.

Reincarnation [edit]

In Jainism, a soul travels to any 1 of the iv states of existence afterwards death depending on its karmas.

Reincarnation is the philosophical or religious concept that an aspect of a living being starts a new life in a different physical trunk or grade afterward each biological death. It is also called rebirth or transmigration, and is a part of the Saṃsāra doctrine of circadian existence.[66] [67] It is a central tenet of all major Indian religions, namely Jainism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sikhism.[67] [68] [69] The idea of reincarnation is constitute in many aboriginal cultures,[70] and a belief in rebirth/metempsychosis was held by Greek historic figures, such equally Pythagoras, Socrates, and Plato.[71] It is also a common belief of various ancient and modern religions such as Spiritism, Theosophy, and Eckankar, and as an esoteric conventionalities in many streams of Orthodox Judaism. It is plant as well in many tribal societies around the world, in places such equally Australia, E Asia, Siberia, and South America.[72]

Although the majority of denominations within Christianity and Islam exercise not believe that individuals reincarnate, particular groups within these religions do refer to reincarnation; these groups include the mainstream historical and gimmicky followers of Cathars, Alawites, the Druze,[73] and the Rosicrucians.[74] The historical relations between these sects and the beliefs near reincarnation that were characteristic of Neoplatonism, Orphism, Hermeticism, Manicheanism, and Gnosticism of the Roman era besides as the Indian religions have been the field of study of recent scholarly research.[75] Unity Church building and its founder Charles Fillmore teaches reincarnation.

In recent decades, many Europeans and North Americans have developed an interest in reincarnation,[76] and many contemporary works mention it.

Karma [edit]

Karma (; Sanskrit: कर्म, romanized: karma , IPA: [ˈkɐɽmɐ] ( ![]() listen ); Pali: kamma) means action, work or deed;[77] it besides refers to the spiritual principle of cause and consequence where intent and deportment of an individual (crusade) influence the future of that individual (effect).[78] Good intent and good deeds contribute to good karma and future happiness, while bad intent and bad deeds contribute to bad karma and hereafter suffering.[79] [80]

listen ); Pali: kamma) means action, work or deed;[77] it besides refers to the spiritual principle of cause and consequence where intent and deportment of an individual (crusade) influence the future of that individual (effect).[78] Good intent and good deeds contribute to good karma and future happiness, while bad intent and bad deeds contribute to bad karma and hereafter suffering.[79] [80]

With origins in aboriginal India's Vedic civilization, the philosophy of karma is closely associated with the idea of rebirth in many schools of Indian religions (particularly Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism[81]) as well as Taoism.[82] In these schools, karma in the present affects 1's hereafter in the current life, as well as the nature and quality of future lives – one'southward saṃsāra.[83] [84]

Christian theology [edit]

In Catholic theology, the supernatural guild is, co-ordinate to New Advent, divers every bit "the ensemble of furnishings exceeding the powers of the created universe and gratuitously produced by God for the purpose of raising the rational creature above its native sphere to a God-like life and destiny."[86] The Modern Catholic Lexicon defines it as "the sum full of heavenly destiny and all the divinely established means of reaching that destiny, which surpass the mere powers and capacities of human being nature."[87]

Process theology [edit]

Process theology is a school of idea influenced by the metaphysical process philosophy of Alfred Due north Whitehead (1861–1947) and further adult by Charles Hartshorne (1897–2000).

It is not possible, in process metaphysics, to conceive divine activity as a "supernatural" intervention into the "natural" order of events. Process theists normally regard the stardom between the supernatural and the natural as a by-product of the doctrine of creation ex nihilo. In process thought, there is no such affair every bit a realm of the natural in contrast to that which is supernatural. On the other hand, if "the natural" is divers more neutrally every bit "what is in the nature of things," and then procedure metaphysics characterizes the natural equally the artistic activeness of actual entities. In Whitehead'south words, "It lies in the nature of things that the many enter into complex unity" (Whitehead 1978, 21). It is tempting to emphasize procedure theism's denial of the supernatural and thereby highlight that the processed God cannot do in comparison what the traditional God could do (that is, to bring something from nothing). In fairness, nevertheless, equal stress should be placed on process theism's denial of the natural (equally traditionally conceived) and then that one may highlight what the creatures cannot practise, in traditional theism, in comparing to what they can exercise in process metaphysics (that is, to exist function creators of the world with God).[88]

—Donald Viney, "Process Theism" in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Heaven [edit]

Heaven, or the heavens, is a common religious, cosmological, or transcendent identify where beings such as gods, angels, spirits, saints, or venerated ancestors are said to originate, exist enthroned, or alive. According to the beliefs of some religions, heavenly beings can descend to Earth or incarnate, and earthly beings tin arise to heaven in the afterlife, or in exceptional cases enter heaven alive.

Heaven is often described as a "higher place", the holiest place, a Paradise, in contrast to hell or the Underworld or the "low places", and universally or conditionally attainable by earthly beings according to various standards of divinity, goodness, piety, faith, or other virtues or right beliefs or simply the will of God. Some believe in the possibility of a sky on Earth in a world to come.

Another belief is in an axis mundi or world tree which connects the heavens, the terrestrial world, and the underworld. In Indian religions, sky is considered as Svarga loka,[89] and the soul is again subjected to rebirth in unlike living forms according to its karma. This cycle can be broken later on a soul achieves Moksha or Nirvana. Whatsoever place of being, either of humans, souls or deities, exterior the tangible world (Heaven, Hell, or other) is referred to as otherworld.

Underworld [edit]

The underworld is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions, located below the globe of the living.[90] Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underworld.

The concept of an underworld is found in almost every civilisation and "may be as old every bit humanity itself".[91] Common features of underworld myths are accounts of living people making journeys to the underworld, ofttimes for some heroic purpose. Other myths reinforce traditions that entrance of souls to the underworld requires a proper observation of ceremony, such equally the ancient Greek story of the recently dead Patroclus haunting Achilles until his body could be properly buried for this purpose.[92] Persons having social status were dressed and equipped in order to better navigate the underworld.[93]

A number of mythologies comprise the concept of the soul of the deceased making its own journey to the underworld, with the dead needing to exist taken across a defining obstacle such every bit a lake or a river to attain this destination.[94] Imagery of such journeys tin be constitute in both aboriginal and mod art. The descent to the underworld has been described every bit "the single nearly of import myth for Modernist authors".[95]

Spirit [edit]

A spirit is a supernatural being, often just not exclusively a non-physical entity; such every bit a ghost, fairy, or angel.[96] The concepts of a person's spirit and soul, often also overlap, as both are either assorted with or given ontological priority over the body and both are believed to survive actual expiry in some religions,[97] and "spirit" can too have the sense of "ghost", i.e. a manifestation of the spirit of a deceased person. In English Bibles, "the Spirit" (with a capital letter "South"), specifically denotes the Holy Spirit.

Spirit is oft used metaphysically to refer to the consciousness or personality.

Historically, it was besides used to refer to a "subtle" as opposed to "gross" material substance, as in the famous final paragraph of Sir Isaac Newton'south Principia Mathematica.[98]

Demon [edit]

A demon (from Koine Greek δαιμόνιον daimónion) is a supernatural and often malevolent being prevalent in religion, occultism, literature, fiction, mythology and folklore.

In Aboriginal Near Eastern religions too as in the Abrahamic traditions, including aboriginal and medieval Christian demonology, a demon is considered a harmful spiritual entity, beneath the heavenly planes[99] which may crusade demonic possession, calling for an exorcism. In Western occultism and Renaissance magic, which grew out of an amalgamation of Greco-Roman magic, Jewish Aggadah and Christian demonology,[100] a demon is believed to be a spiritual entity that may be conjured and controlled.

Magic [edit]

Magic or sorcery is the use of rituals, symbols, actions, gestures, or language with the aim of utilizing supernatural forces.[101] [102] : vi–7 [103] [104] : 24 Belief in and practice of magic has been present since the earliest human being cultures and continues to take an important spiritual, religious, and medicinal office in many cultures today. The term magic has a variety of meanings, and there is no widely agreed upon definition of what it is.

Scholars of religion have defined magic in different ways. 1 approach, associated with the anthropologists Edward Tylor and James Grand. Frazer, suggests that magic and science are opposites. An alternative approach, associated with the sociologists Marcel Mauss and Emile Durkheim, argues that magic takes place in individual, while religion is a communal and organised activity. Many scholars of religion have rejected the utility of the term magic and it has become increasingly unpopular within scholarship since the 1990s.

The term magic comes from the Old Farsi magu, a word that applied to a form of religious functionary about which lilliputian is known. During the late sixth and early fifth centuries BCE, this term was adopted into Aboriginal Greek, where it was used with negative connotations, to apply to religious rites that were regarded as fraudulent, unconventional, and dangerous. This pregnant of the term was and so adopted past Latin in the showtime century BCE. The concept was and then incorporated into Christian theology during the offset century CE, where magic was associated with demons and thus defined against faith. This concept was pervasive throughout the Eye Ages, although in the early modern catamenia Italian humanists reinterpreted the term in a positive sense to institute the idea of natural magic. Both negative and positive understandings of the term were retained in Western civilization over the following centuries, with the former largely influencing early on academic usages of the word.

Throughout history, there have been examples of individuals who practiced magic and referred to themselves as magicians. This trend has proliferated in the modern period, with a growing number of magicians appearing inside the esoteric milieu.[ not verified in body ] British esotericist Aleister Crowley described magic as the art of effecting change in accordance with volition.

Divination [edit]

Divination (from Latin divinare "to foresee, to be inspired past a god",[105] related to divinus, divine) is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by manner of an occultic, standardized procedure or ritual.[106] Used in various forms throughout history, diviners ascertain their interpretations of how a querent should keep by reading signs, events, or omens, or through declared contact with a supernatural agency.[107]

Divination can be seen as a systematic method with which to organize what appear to be disjointed, random facets of being such that they provide insight into a problem at manus. If a distinction is to be made between divination and fortune-telling, divination has a more formal or ritualistic element and frequently contains a more than social character, usually in a religious context, as seen in traditional African medicine. Fortune-telling, on the other hand, is a more everyday do for personal purposes. Particular divination methods vary past culture and organized religion.

Divination is dismissed by the scientific community and skeptics equally existence superstition.[108] [109] In the 2nd century, Lucian devoted a witty essay to the career of a adventurer, "Alexander the false prophet", trained by "one of those who advertise enchantments, miraculous incantations, charms for your love-diplomacy, visitations for your enemies, disclosures of buried treasure, and successions to estates".[110]

Witchcraft [edit]

Witchcraft or witchery broadly ways the practice of and belief in magical skills and abilities exercised by solitary practitioners and groups. Witchcraft is a broad term that varies culturally and societally, and thus tin exist hard to define with precision,[111] and cross-cultural assumptions about the significant or significance of the term should be applied with caution. Witchcraft often occupies a religious divinatory or medicinal role,[112] and is frequently nowadays inside societies and groups whose cultural framework includes a magical world view.[111]

Phenomenon [edit]

A phenomenon is an event not explicable by natural or scientific laws.[113] Such an event may be attributed to a supernatural being (a deity), a miracle worker, a saint or a religious leader.

Informally, the word "miracle" is oft used to characterise any beneficial effect that is statistically unlikely but not contrary to the laws of nature, such as surviving a natural disaster, or but a "wonderful" occurrence, regardless of likelihood, such every bit a birth. Other such miracles might be: survival of an illness diagnosed as terminal, escaping a life-threatening situation or 'beating the odds'. Some coincidences may be seen as miracles.[114]

A true miracle would, by definition, be a not-natural phenomenon, leading many rational and scientific thinkers to dismiss them as physically impossible (that is, requiring violation of established laws of physics within their domain of validity) or impossible to confirm past their nature (because all possible concrete mechanisms can never be ruled out). The one-time position is expressed for example by Thomas Jefferson and the latter past David Hume. Theologians typically say that, with divine providence, God regularly works through nature still, every bit a creator, is costless to work without, in a higher place, or confronting it as well. The possibility and probability of miracles are then equal to the possibility and probability of the existence of God.[115]

Skepticism [edit]

Skepticism (American English language) or scepticism (British English; run across spelling differences) is generally any questioning attitude or dubiousness towards one or more items of putative knowledge or belief.[116] [117] Information technology is often directed at domains such as the supernatural, morality (moral skepticism), religion (skepticism about the being of God), or knowledge (skepticism about the possibility of knowledge, or of certainty).[118] Formally, skepticism as a topic occurs in the context of philosophy, particularly epistemology, although it can be applied to any topic such as politics, religion, and pseudoscience.

One reason why skeptics affirm that the supernatural cannot exist is that annihilation "supernatural" is non a part of the natural world simply by definition. Although some believers in the supernatural insist that information technology simply cannot be demonstrated using the existing scientific methods, skeptics assert that such methods is the best tool humans have devised for knowing what is and isn't knowable.[119]

In fiction and pop culture [edit]

Supernatural entities and powers are mutual in various works of fantasy. Examples include the television shows Supernatural and The Ten-Files, the magic of the Harry Potter series, The Lord of the Rings serial, The Bicycle of Time series, A Song of Water ice and Burn down series and the Force of Star Wars.

See likewise [edit]

- Journal of Parapsychology

- Liberal naturalism

- Magical thinking

- Parapsychology

- Religious naturalism

- Romanticism

- Spirit photography

References [edit]

- ^ "Definition of SUPERNATURAL".

- ^ a b c d e f Bartlett, Robert (fourteen March 2008). "1. The Boundaries of the Supernatural". The Natural and the Supernatural in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–34. ISBN978-0521702553.

- ^ a b "Supernatural" (Online). A Concise Companion to the Jewish Organized religion. Oxford Reference Online – Oxford University Printing.

The ancients had no word for the supernatural any more than than they had for nature.

- ^ Pasulka, Diana; Kripal, Jeffrey (23 Nov 2014). "Religion and the Paranormal". Oxford University Press blog. Oxford Academy Printing.

- ^ Halman, Loek (2010). "8. Disbelief And Secularity In The Netherlands". In Phil Zuckerman (ed.). Disbelief and Secularity Vol.two: Gloabal Expressions. Praeger. ISBN9780313351839.

"Thus, despite the fact that they claim to be convinced atheists and the bulk deny the beingness of a personal god, a rather large minority of the Dutch convinced atheists believe in a supernatural power!" (e.g. telepathy, reincarnation, life after death, and sky)

- ^ "Naturalism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. University of Tennessee.

However, naturalism is non always narrowly scientistic. There are versions of naturalism that repudiate supernaturalism and diverse types of a priori theorizing without exclusively championing the natural sciences.

- ^ a b "supernatural". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Printing. Retrieved 24 October 2018. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b Saler, Benson (1977). "Supernatural as a Western Category". Ethos. 5: 31–53. doi:10.1525/eth.1977.5.1.02a00040.

- ^ Boyle, Robert; Stewart, Grand.A. (1991). Selected Philosophical Papers of Robert Boyle. HPC Classics Serial. Hackett. pp. 176–177. ISBN978-0-87220-122-iv. LCCN 91025480.

- ^ Roberts, John T. (2010). "Some Laws of Nature are Metaphysically Contingent". Australasian Periodical of Philosophy. 88 (3): 445–457. doi:10.1080/00048400903159016. S2CID 170608423.

- ^ "On the Metaphysical Contingency of Laws of Nature". Conceivability and Possibility. Oxford University Press. 2002. pp. 309–336.

- ^ "The Contingency of Physical Laws". Retrieved 2022-02-11 .

- ^ Partridge, Kenneth (2009). The paranormal. ISBN9780824210922 . Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ^ Winkelman, K.; et al. (February 1982). "Magic: A Theoretical Reassessment [and Comments and Replies]". Current Anthropology. 23 (1): 37–66. doi:10.1086/202778. JSTOR 274255. S2CID 147447041.

- ^ Zhong Yang Yan Jiu Yuan; Min Tsu Hsüeh Yen Chiu So (1976). Bulletin of the Plant of Ethnology, Academia Sinica, Issues 42–44.

- ^ Ellis, B.J.; Bjorklund, D.F. (2004). Origins of the Social Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and Kid Development. Guilford Publications. p. 413. ISBN9781593851033. LCCN 2004022693.

- ^ Legare, Cristine H.; Visala, Aku (2011). "Betwixt Religion and Science: Integrating Psychological and Philosophical Accounts of Explanatory Coexistence". Human Development. 54 (3): 169–184. doi:ten.1159/000329135. S2CID 53668380.

- ^ Legare, Cristine H.; Evans, E. Margaret; Rosengren, Karl S.; Harris, Paul 50. (May 2012). "The Coexistence of Natural and Supernatural Explanations Across Cultures and Evolution: Coexistence of Natural and Supernatural Explanations". Child Evolution. 83 (3): 779–793. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01743.x. hdl:2027.42/91141. PMID 22417318.

- ^ Aizenkot, Dana (xi September 2020). "Pregnant-Making to Child Loss: The Coexistence of Natural and Supernatural Explanations of Death". Journal of Constructivist Psychology. 35: 318–343. doi:10.1080/10720537.2020.1819491. S2CID 225231409.

- ^ Busch, Justin T. A.; Watson-Jones, Rachel E.; Legare, Cristine H. (March 2017). "The coexistence of natural and supernatural explanations within and across domains and evolution". British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 35 (1): 4–20. doi:10.1111/bjdp.12164. PMID 27785818. S2CID 24196030.

- ^ Whitehouse, Harvey (2011). "The Coexistence Problem in Psychology, Anthropology, and Evolutionary Theory". Human Development. 54 (3): 191–199. doi:10.1159/000329149. S2CID 145622566.

- ^ Watson-Jones, Rachel E.; Busch, Justin T. A.; Legare, Cristine H. (October 2015). "Interdisciplinary and Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Explanatory Coexistence". Topics in Cognitive Science. 7 (4): 611–623. doi:ten.1111/tops.12162. PMID 26350158.

- ^ The American Heritage Book of English language Usage: A Practical and Authoritative Guide to Contemporary English. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 1996. p. 219. ISBN978-0395767856.

- ^ O'Brien, Jodi (2009). Encyclopedia of Gender and Society. Los Angeles: SAGE. p. 191. ISBN9781412909167 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Stevenson, Angus (2010). Oxford Lexicon of English (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 461. ISBN9780199571123 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Littleton], C. Scott (2005). Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology. New York: Marshall Cavendish. p. 378. ISBN9780761475590 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Becking, Bob; Dijkstra, Meindert; Korpel, Marjo; Vriezen, Karel (2001). Only One God?: Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah. London: New York. p. 189. ISBN9780567232120 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

The Christian tradition is, in imitation of Judaism, a monotheistic religion. This implies that believers have the beingness of only one God. Other deities either do not exist, are seen as the product of human imagination or are dismissed equally remanents of a persistent paganism

- ^ Korte, Anne-Marie; Haardt, Maaike De (2009). The Boundaries of Monotheism: Interdisciplinary Explorations Into the Foundations of Western Monotheism. BRILL. p. nine. ISBN978-9004173163 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Dark-brown, Jeannine K. (2007). Scripture equally Communication: Introducing Biblical Hermeneutics. Bakery Bookish. p. 72. ISBN9780801027888 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Taliaferro, Charles; Harrison, Victoria South.; Goetz, Stewart (2012). The Routledge Companion to Theism. Routledge. pp. 78–79. ISBN9781136338236 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Reat, North. Ross; Perry, Edmund F. (1991). A World Theology: The Central Spiritual Reality of Humankind . Cambridge Academy Press. pp. 73–75. ISBN9780521331593 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Keown, Damien (2013). Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction (New ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN9780199663835 . Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ a b Bullivant, Stephen; Ruse, Michael (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Atheism. Oxford University Publishing. ISBN9780199644650 . Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ a b Hood, Robert E. (1990). Must God Remain Greek?: Afro Cultures and God-talk. Minneapolis: Fortress Printing. pp. 128–129. ISBN9780800624491.

African people may draw their deities as strong, but not omnipotent; wise but not omniscient; one-time simply not eternal; great but not omnipresent (...)

- ^ a b Trigger, Bruce Thousand. (2003). Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Written report (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 441–442. ISBN9780521822459.

[Historically...] people perceived far fewer differences betwixt themselves and the gods than the adherents of modernistic monotheistic religions. Deities were not thought to be omniscient or omnipotent and were rarely believed to be changeless or eternal

- ^ John Murdoch, English Translations of Select Tracts, Published in Bharat – Religious Texts at Google Books, pages 141–142; Quote: "We [monotheists] find by reason and revelation that God is omniscient, omnipotent, near holy, etc, but the Hindu deities possess none of those attributes. It is mentioned in their Shastras that their deities were all vanquished past the Asurs, while they fought in the heavens, and for fearfulness of whom they left their abodes. This plainly shows that they are not omnipotent."

- ^ Taliaferro, Charles; Marty, Elsa J. (2010). A Dictionary of Philosophy of Faith. New York: Continuum. pp. 98–99. ISBN9781441111975.

- ^ Wilkerson, Due west.D. (2014). Walking With The Gods. Sankofa. pp. six–7. ISBN978-0991530014.

- ^ Trigger, Bruce One thousand. (2003). Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 473–474. ISBN9780521822459.

- ^ Kramarae, Cheris; Spender, Dale (2004). Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women: Global Women'due south Problems and Knowledge. Routledge. p. 655. ISBN9781135963156 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ O'Brien, Julia Chiliad. (2014). Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and Gender Studies. Oxford Academy Press, Incorporated. ISBN9780199836994 . Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ Bonnefoy, Yves (1992). Roman and European Mythologies . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 274–275. ISBN9780226064550 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Pintchman, Tracy (2014). Seeking Mahadevi: Constructing the Identities of the Hindu Bully Goddess. SUNY Press. pp. ane–two, 19–20. ISBN9780791490495 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Roberts, Nathaniel (2016). To Be Cared For: The Power of Conversion and Foreignness of Belonging in an Indian Slum. University of California Press. p. xv. ISBN9780520963634 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Malandra, William W. (1983). An Introduction to Ancient Iranian Religion: Readings from the Avesta and the Achaemenid Inscriptions. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 9–ten. ISBN978-0816611157 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Fløistad, Guttorm (2010). Volume 10: Philosophy of Religion (1st ed.). Dordrecht: Springer Scientific discipline & Business Media B.V. pp. nineteen–20. ISBN9789048135271 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Daniel T. Potts (1997). Mesopotamian Culture: The Material Foundations. Cornell University Press. pp. 186–187. ISBN978-0-8014-3339-9.

- ^ Potter, Karl H. (2014). The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume iii: Advaita Vedanta upward to Samkara and His Pupils. Princeton Academy Press. pp. 272–274. ISBN9781400856510 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Olivelle, Patrick (2006). The Samnyasa Upanisads: Hindu Scriptures on Divineness and Renunciation. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN9780195361377 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Cush, Denise; Robinson, Catherine; York, Michael (2008). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. London: Routledge. pp. 899–900. ISBN9781135189792 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ The Gratis Dictionary [i] retrieved 1 September 2012

- ^ "Angels in Christianity." Religion Facts. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 December. 2014

- ^ [2]Augustine of Hippo'due south Enarrationes in Psalmos, 103, I, 15, augustinus.information technology (in Latin)

- ^ "Definition of Angel". www.merriam-webster.com . Retrieved 2016-05-02 .

- ^ "ANGELOLOGY - JewishEncyclopedia.com". jewishencyclopedia.com . Retrieved 2016-05-02 .

- ^ Proverbio(2007), pp. 90–95; cf. review in La Civiltà Cattolica, 3795–3796 (2–16 August 2008), pp. 327–328.

- ^ Didron, Vol 2, pp.68–71

- ^ Beale G.M., The Book of Revelation, NIGTC, Grand Rapids – Cambridge 1999. = ISBN 0-8028-2174-X

- ^ Esposito, John L. What Everyone Needs to Know virtually Islam (New York: Oxford Academy Press, 2002), pp. 7–eight.

- ^ Lambert, Gray (2013). The Leaders Are Coming!. WestBow Press. p. 287. ISBN9781449760137.

- ^ Roy H. Williams; Michael R. Drew (2012). Pendulum: How By Generations Shape Our Nowadays and Predict Our Time to come. Vanguard Press. p. 143. ISBN9781593157067.

- ^ Maria Valtorta, The Poem of the Homo God, ISBN 99926-45-57-1

- ^ Michael Freze, 1993, Voices, Visions, and Apparitions, OSV Publishing ISBN 0-87973-454-Ten p. 252

- ^ Michael Freze, 1989 They Bore the Wounds of Christ ISBN 0-87973-422-1

- ^ "Revelation | Define Revelation at Dictionary.com". Lexicon.reference.com. Retrieved 2013-07-fourteen .

- ^ Norman C. McClelland 2010, pp. 24–29, 171. sfn mistake: no target: CITEREFNorman_C._McClelland2010 (aid)

- ^ a b Mark Juergensmeyer & Wade Clark Roof 2011, pp. 271–272. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMark_JuergensmeyerWade_Clark_Roof2011 (help)

- ^ Stephen J. Laumakis 2008, pp. xc–99. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStephen_J._Laumakis2008 (aid)

- ^ Rita Thousand. Gross (1993). Buddhism After Patriarchy: A Feminist History, Analysis, and Reconstruction of Buddhism . State University of New York Printing. pp. 148. ISBN978-one-4384-0513-one.

- ^ Norman C. McClelland 2010, pp. 102–103. sfn error: no target: CITEREFNorman_C._McClelland2010 (help)

- ^ see Charles Taliaferro, Paul Draper, Philip Fifty. Quinn, A Companion to Philosophy of Religion. John Wiley and Sons, 2010, folio 640, Google Books

- ^ Gananath Obeyesekere, Imagining Karma: Ethical Transformation in Amerindian, Buddhist, and Greek Rebirth. University of California Press, 2002, folio 15.

- ^ Hitti, Philip K (2007) [1924]. Origins of the Druze People and Religion, with Extracts from their Sacred Writings (New Edition). Columbia Academy Oriental Studies. 28. London: Saqi. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-86356-690-ane

- ^ Heindel, Max (1985) [1939, 1908] The Rosicrucian Christianity Lectures (Collected Works): The Riddle of Life and Decease. Oceanside, California. fourth edition. ISBN 0-911274-84-7

- ^ An of import recent piece of work discussing the mutual influence of ancient Greek and Indian philosophy regarding these matters is The Shape of Aboriginal Thought by Thomas McEvilley

- ^ "Pop psychology, belief in life later on death and reincarnation in the Nordic countries, Western and Eastern Europe" (PDF). (54.eight KB)

- ^ See:

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th Edition, Book fifteen, New York, pp 679–680, Article on Karma; Quote – "Karma meaning act or activity; in addition, it too has philosophical and technical meaning, denoting a person's deeds as determining his future lot."

- The Encyclopedia of World Religions, Robert Ellwood & Gregory Alles, ISBN 978-0-8160-6141-nine, pp 253; Quote – "Karma: Sanskrit discussion meaning action and the consequences of action."

- Hans Torwesten (1994), Vedanta: Heart of Hinduism, ISBN 978-0802132628, Grove Press New York, pp 97; Quote – "In the Vedas the word karma (work, deed or action, and its resulting event) referred mainly to..."

- ^ Karma Encyclopædia Britannica (2012)

- ^ Halbfass, Wilhelm (2000), Karma und Wiedergeburt im indischen Denken, Diederichs, München, Germany

- ^ Lawrence C. Becker & Charlotte B. Becker, Encyclopedia of Ideals, 2nd Edition, ISBN 0-415-93672-1, Hindu Ethics, pp 678

- ^ Parvesh Singla. The Manual of Life – Karma. Parvesh singla. pp. five–seven. GGKEY:0XFSARN29ZZ. Retrieved four June 2011.

- ^ Eva Wong, Taoism, Shambhala Publications, ISBN 978-1590308820, pp. 193

- ^ "Karma" in: John Bowker (1997), The Concise Oxford Lexicon of Earth Religions, Oxford University Printing.

- ^ James Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Rosen Publishing, New York, ISBN 0-8239-2287-ane, pp 351–352

- ^ Pastrovicchi, Angelo (1918). Rev. Francis Southward. Laing (ed.). St. Joseph of Copertino. St. Louis: B.Herder. p. four. ISBN978-0-89555-135-1.

- ^ Sollier, J. "Supernatural Order". Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2008-09-11 .

- ^ Hardon, Fr. John. "Supernatural Lodge". Eternal Life. Retrieved 2008-09-15 .

- ^ Viney, Donald (2008). "Process Theism". In Edward N. Zalta (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Wintertime 2008 ed.).

- ^ "Life After Expiry Revealed – What Really Happens in the Afterlife". SSRF English . Retrieved 2018-03-22 .

- ^ "Underworld". The gratuitous dictionary . Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ^ Isabelle Loring Wallace, Jennie Hirsh, Gimmicky Fine art and Classical Myth (2011), p. 295.

- ^ Radcliffe G. Edmonds, III, Myths of the Underworld Journey: Plato, Aristophanes, and the 'Orphic' Gilt Tablets (2004), p. nine.

- ^ Jon Mills, Underworlds: Philosophies of the Unconscious from Psychoanalysis to Metaphysics (2014), p. 1.

- ^ Evans Lansing Smith, The Descent to the Underworld in Literature, Painting, and Film, 1895–1950 (2001), p. 257.

- ^ Evans Lansing Smith, The Descent to the Underworld in Literature, Painting, and Film, 1895–1950 (2001), p. 7.

- ^ François 2008, p.187-197.

- ^ OED "spirit 2.a.: The soul of a person, as commended to God, or passing out of the body, in the moment of death."

- ^ Burtt, Edwin A. (2003). Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Physical Science. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. p. 275.

- ^ South. T. Joshi Icons of Horror and the Supernatural: An Encyclopedia of Our Worst Nightmares, Band Greenwood Publishing Grouping 2007 ISBN 978-0-313-33781-ix page 34

- ^ See, for case, the course synopsis and bibliography for "Magic, Science, Religion: The Evolution of the Western Esoteric Traditions" Archived Nov 29, 2014, at the Wayback Car, at Key European Academy, Budapest

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (1995). The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy (Reprint ed.). Oxford; Cambridge: Blackwell. pp. 289–291, 335. ISBN978-0631189466.

- ^ Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja (1991). Magic, Science, Organized religion, and the Scope of Rationality (Reprint ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN978-0521376310.

- ^ Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (2006). Lexicon of Gnosis & Western Esotericism (Unabridged ed.). Leiden: Brill. p. 718. ISBN978-9004152311.

- ^ Mauss, Marcel; Bain, Robert; Pocock, D. F. (2007). A General Theory of Magic (Reprint ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN978-0415253963.

- ^ "LacusCurtius • Greek and Roman Divination (Smith'southward Dictionary, 1875)". uchicago.edu.

- ^ Peek, P.M. African Divination Systems: Means of Knowing. page two. Indiana University Press. 1991.

- ^ Silva, Sónia (2016). "Object and Objectivity in Divination". Textile Religion. 12 (four): 507–509. doi:x.1080/17432200.2016.1227638. ISSN 1743-2200. S2CID 73665747.

- ^ Yau, Julianna. (2002). Witchcraft and Magic. In Michael Shermer. The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience. ABC-CLIO. pp. 278–282. ISBN 1-57607-654-seven

- ^ Royal, Brian. (2009). Pseudoscience: A Disquisitional Encyclopedia. Greenwood. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-313-35507-3

- ^ "Lucian of Samosata : Alexander the False Prophet". tertullian.org.

- ^ a b Witchcraft in the Heart Ages, Jeffrey Russell, p.4-10.

- ^ Bengt Ankarloo & Stuart Clark, Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: Biblical and Pagan Societies", University of Philadelphia Printing, 2001

- ^ Miracle

- ^ Halbersam, Yitta (1890). Small Miracles. Adams Media Corp. ISBN978-1-55850-646-6.

- ^ Miracles on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Popkin, R. H. "The History of Skepticism from Erasmus to Descartes (rev. ed. 1968); C. L. Stough, Greek Skepticism (1969); G. Burnyeat, ed., The Skeptical Tradition (1983); B. Stroud, The Significance of Philosophical Skepticism (1984)". Encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com.

- ^ "Philosophical views are typically classed equally skeptical when they involve advancing some caste of doubt regarding claims that are elsewhere taken for granted." utm.edu

- ^ Greco, John (2008). The Oxford Handbook of Skepticism. Oxford University Press, The states. ISBN9780195183214.

- ^ Novella, Steven, et al. The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe: How to Know What's Really Existent in a World Increasingly Full of False. K Central Publishing, 2018. pp. 145–146.

Further reading [edit]

- Economic Production and the Spread of Supernatural Beliefs ~ Daniel Araújo January 7, 2022

- Bouvet R, Bonnefon J. F. (2015). "Non-Reflective Thinkers Are Predisposed to Attribute Supernatural Causation to Uncanny Experiences". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 41 (7): 955–61. doi:10.1177/0146167215585728. PMID 25948700. S2CID 33570482.

- McNamara P, Bulkeley K (2015). "Dreams as a Source of Supernatural Agent Concepts". Frontiers in Psychology. half-dozen: 283. doi:x.3389/fpsyg.2015.00283. PMC4365543. PMID 25852602.

- Riekki T, Lindeman K, Raij T. T. (2014). "Supernatural Believers Attribute More Intentions to Random Move than Skeptics: An fMRI Study". Social Neuroscience. 9 (4): 400–411. doi:10.1080/17470919.2014.906366. PMID 24720663. S2CID 33940568.

{{cite periodical}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Purzycki Benjamin G (2013). "The Minds of Gods: A Comparative Report of Supernatural Agency". Cognition. 129 (1): 163–179. doi:ten.1016/j.noesis.2013.06.010. PMID 23891826. S2CID 23554738.

- Thomson P, Jaque S. Five. (2014). "Unresolved Mourning, Supernatural Beliefs and Dissociation: A Mediation Analysis". Attachment and Human Development. 16 (v): 499–514. doi:10.1080/14616734.2014.926945. PMID 24913392. S2CID 10290610.

- Vail K. E, Arndt J, Addollahi A. (2012). "Exploring the Existential Function of Organized religion and Supernatural Agent Beliefs Amidst Christians, Muslims, Atheists, and Agnostics". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 38 (ten): 1288–1300. doi:10.1177/0146167212449361. PMID 22700240. S2CID 2019266.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors listing (link)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supernatural

0 Response to "Could the Evolutionary Theory of the Development of Humankind Include the Ability to Make Art?"

Post a Comment